A Divine Dance

Kamakshi asked the auto driver to go a little slowly, her eyes anxiously searching for the elusive Post office. “Where is it Amma?” said the auto driver and drove in fits and starts and revved the engine ferociously.

“You made me go to the Main Post Office on 100 feet Road and wait for ten minutes before you found out that it was not the one you are looking for.”

“It’s on 13th Main, not on 100 feet Road.”

“Amma, Indiranagar is a large locality, it has several post offices, and don’t you have the correct address? Wasting my time, so much petrol gets consumed”.

“We are almost there, take a turn here, it must be this road,” said Kamakshi, anxiously wiping her face.

To her relief, she finally found it opposite the Sai Baba Temple. She paid the driver a bit extra to placate him and walked in. She lived in Malleshwaram and had no idea, why her husband, Srini should purchase National Savings Certificates from the Indiranagar Branch.

“Kamu, you will have to go personally and encash the certificates. It’s a sizeable amount not to be sneezed at,” said Srini.

It was a relief to get away from home, a brief respite from constantly looking after an invalid. And Srini wasn’t an easy one. Clingy, cantankerous and corpulent. She hated it when she had to lift his flabby arms to powder the cracks and crevices hiding beneath those masses of flesh and the strange odour they emanated, like a cheap Chinese restaurant that smelled of soy sauce. And Srini wouldn’t help, not a bit, watching her with an expressionless glee, as she fought a relentless battle against the bulges and folds that refused to cooperate.

Bangalore was terrible in March, hot and humid, almost everyone snivelling with a cold and cough from the pollen that floated around, until it was washed away by the first showers of summer. She walked into the post office to find it filled to capacity with customers, standing in coiling queues that folded in on themselves and stretched out, as if they had a life of its own. She managed to find the right counter and stood patiently for 30 minutes and nervously extending the certificates to the already irritated clerk behind the counter.

Just as Kamakshi pushed the certificates through the gap between the counter and the glass panel above, the power went off. The clerk visibly happy that he could now go on his unanticipated break, said, “Sorry, madam, you will have to wait. I cannot access the computer now, and we cannot print out a cheque till the power is back on.”

“But sir…”

The clerk had already moved away, hailing out to his passing colleague to join him for a smoke and a tea at the neighbouring tea stall.

“We’ve been waiting for ever. These Government offices, the staff are looking for an excuse not to work. How lucky for them, that the power had to go off just before lunch?” said the customer waiting behind Kamakshi.

There was absolutely no place to sit down and she pushed her way through the surging crowd to make her way outside. Kamakshi stood indecisively for a minute, hemmed in by the crowd. Someone stepped on her foot and she almost fell over.

She couldn’t wait here, but where would she go? And how long would she have to wait?

“Should I go home? But I’ll have to come again. And who will look after Srini?”

She walked out onto the main 100 feet road and walked aimlessly for a few minutes. This was a commercial area with restaurants with unpronounceable names, boutiques which sold clothes at atrocious prices, beauty salons which could dissuade and intimidate even women most comfortable in their skins from entering, and commercial office space with glass fronted facades and obscene rentals.

The wide road was lined with many trees, the boughs hung heavy with flowers, the many hues and variations of blues, reds, violets and yellows arching over, providing immense shade. But even the overhead canopy was not enough to negate the overwhelming heat; Kamakshi felt the wetness blooming beneath her arms and behind her knees.

“Where can I go? Maybe a restaurant, maybe I can order a cold drink.”

But every restaurant she walked past, she saw young people, half her age grouped around tables. They looked like they belonged there; they fit in with the chic décor. The confidence they exuded amazed her, she could have never managed that when she was their age.

Suddenly the signboard on a small gate on the side attracted her attention.

“Succinct Space: An Alternate Gallery,” it said.

She took a quick peek and saw a narrow staircase sneaking its way up. She looked up and saw a few paintings displayed by the floor to ceiling windows. She hesitated for a second, quickly pushed open the door and made her way up, afraid that she would hear a voice from below demanding to know where she was going.

At the top of the stairs was a colourfully painted wooden door, which said, “Welcome.” She pushed it open; the doorbell jangled, and entered the cool confines of the gallery. She hesitantly looked around, the space appeared empty of people, but was crammed with different types of art works. She moved carefully afraid that she would knock something over.

“Hello, can I help you?” said a friendly voice and she turned around to see a young woman wearing her hair in braids and a strappy top and long skirt. Kamakshi caught a look of surprise and something else, an emotion she couldn’t discern, before the young woman masked her face and looked at her with polite enquiry.

Kamakshi knew she did not quite fit the profile of a person who would frequent such a space. She was a mousy looking middle-aged woman, slightly overweight, with scraggly salt and pepper hair scrunched into an untidy bun. On her nose perched a pair of oval glasses, which were at least five years old, and on the verge of falling apart. She was wearing a crumpled cotton sari with a faded blouse that had seen better days, worn slightly high, so that the edges won’t get dirty and on her feet were a pair of solid black slippers, comfortable but definitely not pleasing to the eye.

“Oh, just looking around, thank you,” said Kamakshi.

The young girl said, “Ok let me know if you need any help. I am right here”, she said gesturing to the small office tucked away in the corner.

Kamakshi hurriedly turned away, thankful at being left alone and almost knocked over a small wooden sculpture of Buddha. She caught it in time, straightened it, wiped her forehead in a nervous gesture and was happy to feel the cool air conditioned breeze swirling around her body, gradually evapourating the sweat from her body.

She walked around and saw paintings and sculptures interspersed with other forms of art – old photographs and new, brass artefacts from a bygone era displayed in the drawing rooms of the rich and the wannabes, and installations which were bizarre yet eye catching. Yes, she knew what installations were, she had read about them in the Sunday Magazine section of the Hindu.

Kamakshi didn’t remember when she had last been in an art gallery, probably during her schooling in Chennai when she was taken to the Egmore Museum. Kamakshi had laughed along with her friends at the abstract pieces they hadn’t understood.

“Look at that painting, isn’t it weird, the eyes seem to be painted on the bum of the figure. The artist was probably high when he was painting.”

Even the teachers accompanying them looked bored and everyone was glad to get out of the stuffy, gloomy environment and head back home.

Kamakshi walked past several paintings – abstracts, still life, contemporary and religious scenes, Indian and western. Even she with her inexperienced eye, found some attractive, was indifferent to others and repulsed by a few.

As she turned a corner and was almost back at the door again, a painting caught her eye. It was not a very large painting and was mounted on a simple black frame. Maybe that was what caught her attention. Many of the others had rather ornate frames.

Two bearded men wearing red turbans and long white gowns were dancing on a blue tiled floor against an arched doorway, which seemed to lead somewhere or maybe nowhere. The combination of colours, the browns and blues, the whites and the reds and all the other hues seemed to somehow come together in a pleasing interpretation. Kamakshi peered at the bottom of the painting and could discern the initial of the artist who painted it. MA it said, an initial and nothing more.

“It’s a painting of sufi dancers. They are from Iran, the dancers I mean. The painting is by a promising young artist,” said a voice from behind and Kamakshi turned around to see the girl who had greeted her, standing at her shoulder.

“They are called whirling dervishes and they twirl around and dance as part of a religious ceremony and go into a kind of trance to seek oneness with God.”

“Merge with the divine,” murmured Kamakshi and the girl looked at her with surprise and said, “Yes, it is said as they dance, they abandon their egos. Their full skirts whirl higher and higher and are an embodiment of the egos shroud.”

The dancers arms were extended wide, the artists had captured them as if they were in an arc, one arm extended to heaven, the other to earth. The limbs were a bit contorted and were bent at seemingly impossible angles, but there was a strange beauty in the rendering.

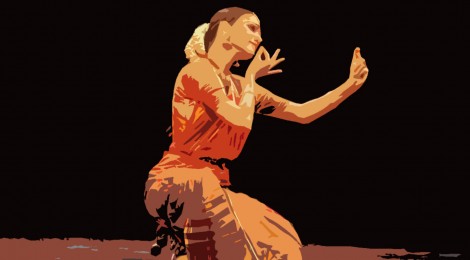

Kamakshi remembered another pair of arms stretched out parallel to the shoulders, palms ending in a pataka pose, knees bent in arremundi position, and heels together with the feet pointing outwards. The rhythmic sound of the stick hitting the wooden block; its perfect marriage with the Natuvangam and the stamping of her feet. The kohl rimmed eyes, the exquisite temple jewellery, the pleated skirt which spread out like a fan when the legs were outstretched, the alta on the fingers, and the Gholusu, making the jal jal sound. How she loved wearing them, and walking around the house?

Her mother would simultaneously delight and frown at these indulgences and say “Kamakshi, keep quiet. Stop that noise, your father is trying to sleep.”

The outer door jangled and Kamakshi suddenly became aware of her surroundings.

“Ma’am, are you okay?” asked the girl and before she could answer led her to a chair and got her a glass of water. Kamakshi gulped down the water, splashing some on her sari and then before she could stop herself said, “I’m fine. I was reminiscing about when I used to dance.”

“You’re a dancer?” asked the girl, “So am I. I am into contemporary and hip hop dance though.”

“Oh! I haven’t danced in many years, I learned Bharatnatyam, even did my Arangetram, but had to give it up years ago. I loved dancing and this painting reminded me of the dance I loved the most, the Thillana, which I would perform at the end of the recital.”

“I am learning Bharatnatyam now, I learned Odissi as a child, but Bharatnatyam has helped widen my repertoire. But why did you have to give it up?”

“Oh, after I got married, my in-laws and husband who were from a conservative background, insisted that I give up dancing. Performing on stage, you see, was not for girls from good families and so I had to give it up. I was not even allowed to go for Bharatnatyam performances,” said Kamakshi, trailing off, embarrassed at having revealed so much.

She got up in an abrupt manner as she couldn’t bear to see the sympathy in the eyes of the young girl, and looking at her watch said, “I must be going. I need to go to the Post Office and then back to Malleshwaram. My husband will be waiting.”

“Please leave your name and number Ma’am, I will notify you if I receive any paintings or other art work related to dance and maybe you could visit us again.”

“Maybe I will,” said Kamakshi and hurriedly walked to the Post Office. It was early afternoon, the crowd had thinned out, the power was back and Kamakshi was able to encash the certificates fairly quickly.

As she entered the house, she heard Srini say, “Where have you been Kamu? It’s past my lunchtime. How long does it take at the Post Office?”

She quickly served him food and then sat down to read the newspaper. She took her time pouring over the news items and finally moved to the arts page, which listed the various events happening in the city. She noticed that Mallavika Sarukkai was performing at the Chowdiah Hall next week. Maybe she would go.

Photograph Courtesy: Fotopedia © Jean-Pierre Dalbera