James Joyce’s Bildungsroman – A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man

I first read James Joyce’s ‘A Portait of the Artist as a Young Man’ when I was seventeen and it changed me, perhaps forever. I was then weaned on a steady diet of Victorian novels, with Jane Austen, Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy ruling the roost. The writer Franz Kafka once said, “A book must be like an axe for the frozen sea inside us.” Joyce’s book had shattered my naïve illusions of what constituted good literature. Jane Austen’s work now seemed like an insipid saga of silly costume dramas and lessons in ‘manners’, replete with young women whose sole purpose in life was to marry the ‘right’ man. Dickens now appeared like a mediocre social commentator with few insights to offer on the complex and layered inner life of his rather interesting characters. Dickens hesitates to get into the mind of his characters and I understood this when I finished reading A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Joyce had decimated the Victorian novel . Literature would not be the same anymore. The literary bar had been raised very high, setting a standard that would challenge future generations of writers.

James Joyce published this novel in 1916 and it was a revised version of an earlier unpublished work of his titled ‘Stephen Hero’. Joyce had nearly destroyed the manuscript of ‘Stephen Hero’ after a bitter altercation with his wife Nora. Thankfully for literature lovers, the manuscript survived the petty tribulations of marital life and Joyce would later use many ideas from ‘Stephen Hero’ in Portrait of the Artist. The novel is a semi-autobiographical work, with many of the episodes based on Joyce’s own experiences in Ireland. It is a coming of age novel which narrates the experiences of a young Irishman Stephen Dedalus from his early childhood till his youth.

Stephen is a clearly a precocious child with an insatiable intellectual curiosity. Joyce gives us a premonition of this even before the novel begins. The book starts with a quote from Ovid’s Metamorphoses – “ Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes”, which translates as ‘..and he sent forth his spirit among the unknown arts.’ This captures the inner life of the protagonist Stephen Dedalus, who is obsessed with the relentless pursuit of truth, beauty and knowledge.

What struck me was Joyce’s style of writing. He brilliantly captures colours, sights and sounds. The novel begins with Stephen’s early childhood. Joyce is able to depict how a child experiences the world around him. Take for instance the experience of bedwetting, which every child finds traumatic, Joyce writes –“When you wet the bed first it is warm and then it gets cold. His mother put on the oilsheet. That had the queer smell”. He makes you think like a child at that moment. There is no ‘distancing’ from the character, where the writer maintains a separation from the protagonists and ‘describes’ what the character is experiencing (like Charles Dickens). Joyce takes the reader into the minds and skins of his characters. Your body tingles with sensations. You experience what the character does. Joyce experiments with language. Stephen’s inner thoughts and feelings during early childhood are described in a language that reflects the young boy’s growing consciousness of the phenomena around him. The prose style mirrors the intellectual growth and transition of the young child Stephan Dedalus into a young adult. This is something one can see in Joyce’s other great work ‘Dubliners’. The initial stories like ‘The Sisters’, ‘An Encounter’ and ‘Araby’ have children as the main protagonists and the prose appears to mirror the age of the protagonists. One feels the transition from childhood and youthful innocence to middle aged maturity when the reader approaches the final story ‘The Dead’.

Joyce’s ‘Portrait’ is a coming of age tale of young Stephen Dedalus who aspires to be an artist. However he is haunted by various doubts about his destiny and the novel is replete with his numerous epiphanies. The novel traces the life of Stephen from his early days at a draconian Jesuit school, where he is indoctrinated to have a blind belief in Christian theology. Joyce brilliantly captures the confusions of young Stephen, when he battles to reconcile his lustful thoughts with his Christian faith. He visits prostitutes regularly and later confesses to the priest his ‘sins’ (when the priest asks him his age, he says “sixteen”).

The initiation of young Stephen into the mysterious world of Irish nationalism is well captured in this passage by Joyce –

On Sundays Stephen with his father and his grand-uncle took their constitutional. The old man was a nimble walker in spite of his corns and often ten or twelve miles of the road were covered. The little village of Stillorgan was the parting of the ways. Either they went to the left towards the Dublin mountains or along the Goatstown road and thence into Dundrum, coming home by Sandyford. Trudging along the road or standing in some grimy wayside public house his elders spoke constantly of the subjects nearer their hearts, of Irish politics, of Munster and of the legends of their own family, to all of which Stephen lent an avid ear. Words which he did not understand he said over and over to himself till he had learnt them by heart: and through them he had glimpses of the real world about them. The hour when he too would take part in the life of that world seemed drawing near and in secret he began to make ready for the great part which he felt awaited him the nature of which he only dimly apprehended.

The descent of his family’s financial circumstances is also well captured. Stephen realizes that he will now have to lead a lower middle class life – “The causes of his embitterment were many, remote and near. He was angry with himself for being young and the prey of restless foolish impulses, angry also with the change of fortune which was reshaping the world about him into a vision of squalor and insincerity. Yet his anger lent nothing to the vision. He chronicled with patience what he saw, detaching himself from it and tasting its mortifying flavour in secret.”

He is a boy growing up in Roman Catholic Ireland, a country which takes religion very seriously. He attends two Jesuit colleges, Clongowes Wood College and Belvedere College, where he is virtually indoctrinated in Christian doctrines. The priests almost succeed. Young Dedalus has a strong urge to join the clergy. This is also in part inspired by guilt. Joyce captures these moments with great skill, when he depicts a sermon by a senior priest Father Arnall. This sermon is about hell and the devil (named Lucifer here). It is one of the most chilling and terrifying passages in literature. Dedalus feels ashamed of his frequent visits to brothels and is virtually converted to the cause of religious dogma. I found this sermon very interesting, especially the reference to Lucifer. Apparently Lucifer (meaning ‘Angel of Light’) was one of the most talented and intelligent of all God’s angels. His expulsion from heaven was based on one single thought that struck him one day. The thought was ‘Non Serviam’ or ‘I will not serve’. This was deemed by God as being too radical and unbecoming of heavenly conduct and Lucifer was expelled. I would interpret this as Joyce’s celebration of the idea of individualism. This seems to mirror Stephen’s own attitude later towards religion. There is a beautiful sentence in the book which captures this idea – “Nothing moved him or spoke to him from the real world unless he heard in it an echo of the infuriated cries within him.”

Stephen’s flirtation with religion ends soon enough. He realizes that his true calling is to become a writer and not a shallow clergyman. He has a rare aptitude, for words. This is pretty clear even at a very young age, when he recollects the words of a song- “A tremor passed over his body. How sad and how beautiful! He wanted to cry quietly but not for himself: for the words, so beautiful and sad, like music”. This is clearly a child with a literary bent of mind!

There is also another amusing incident involving his teacher, an Englishman. Stephen uses a word ‘tundish’, which perplexes his teacher who claims that it is not an English word. However the teacher agrees to the existence of this word, after checking various dictionaries. This sets Stephen to ruminate on the fact that he an Irishman is teaching English to an Englishman! The novel of also about a young man refusing to adhere to social constructs like ‘nation’, ‘family’ and ‘church’. He says – “When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight. You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.” These categories cannot imprison his intellect. He declares emphatically –

I will tell you what I will do and what I will not do. I will not serve that in which I no longer believe, whether it call itself my home, my fatherland, or my church: and I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defense the only arms I allow myself to use –silence, exile and cunning.

These words still invigorate me. We owe loyalty only to truth and all other obligations (be it political or social) are subservient to that calling. This is the lesson I learnt from this great work by Joyce. The book also has one of the most optimistic and life affirming endings in literature – “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” This is a great work written by a literary genius. It certainly deserves your untrammelled attention.

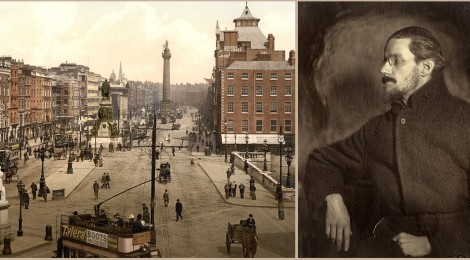

Photography Courtesy: dubliners2013.blogspot.com (Image of Dublin)