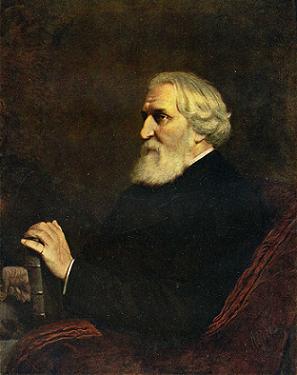

The District Doctor by Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev

ONE day, in autumn, on my way home from the distant fields, I caught cold, and was taken ill. Fortunately, the fever overtook me in the county-town, in the hotel. I sent for the doctor. Half an hour later, the district physician made his appearance, a man of short stature, thin and black-haired. He prescribed for me the customary sudorific, ordered the application of mustard-plasters, very deftly tucked my five-ruble bank-note under his cuff,–but emitted a dry cough and glanced aside as he did so,–and was on the very verge of going off about his own affairs, but somehow got to talking and remained. The fever oppressed me; I foresaw a sleepless night, and was glad to chat with the kindly man. Tea was served. My doctor began to talk. He was far from a stupid young fellow, and expressed himself vigorously and quite entertainingly. Strange things happen in the world: you may live a long time, and on friendly terms, with one man, and never once speak frankly from your soul with him; with another you hardly manage to make acquaintance–and behold: either you have blurted out to him your most secret thoughts, as though you were at confession, or he has blurted out his to you. I know not how I won the confidence of my new friend,–only, without rhyme or reason, as the saying is, he “took” and told me about a rather remarkable occurrence; and now I am going to impart his narrative to the indulgent reader. I shall endeavour to express myself in the physician’s words.

“You are not acquainted,”–he began, in a weak and quavering voice (such is the effect of unadulterated Beryozoff snuff):–“you are not acquainted with the judge here, Pavel Lukitch Myloff, are you? . . . . . You are not? .. . . . . Well, never mind.” (He cleared his throat and wiped his eyes.) “Well, then, please to observe that the affair happened–to be accurate–during the Great Fast, in the very height of the thaw. I was sitting with him at his house, our judge’s, and playing preference. Our judge is a nice man, and fond of playing preference. All of a sudden” (my doctor frequently employed that expression: “all of a sudden”) “I am told: ‘A man is asking for you.’ ‘What does he want?’– said I. They tell me: ‘He has brought a note–it must be from a sick person.’–‘Give me the note,’–said I. And so it proved to be from a sick person. . . . . . Well, very good,–that’s our bread and butter, you understand. . . . . . And this was what was the matter: the person who wrote to me was a landed proprietress, a widow; she says: ‘My daughter is dying, come for the sake of our Lord God, and horses have been sent for you.’ Well, and all that is of no consequence. . . . . But she lives twenty versts from town, night is falling, and the roads are such, that–faugh! And she herself was the poorest of the poor, I couldn’t expect to receive more than two rubles, and even that much was doubtful; and, in all probability, I should be obliged to take a bolt of crash-linen and some scraps or other. However, you understand, duty before everything. All of a sudden, I hand over my cards to Kalliopin, and set off homeward. I look: a wretched little peasant-cart is standing in front of my porch; peasant-horses,–pot-bellied, extremely pot-bellied,–the hair on them a regular matted felt; and the coachman is sitting hatless, by way of respect. Well, thinks I to myself: evidently, brother, thy masters don’t eat off gold. . . . . ..You are pleased to laugh, but I can tell you a poor man, like myself, takes everything into consideration. . . . . If the coachman sits like a prince, and doesn’t doff his cap, and grins in his beard to boot, and waggles his whip, you may bet boldly on getting a couple of bank-bills! But, in this case, I see that the matter does not smack of that. However, thought I to myself, it can’t be helped: duty before everything. I catch up the most indispensable remedies, and set out. Will you believe it, we barely managed to drag ourselves to our goal. The road was hellish: brooks, snow, mud, water-washed gullies; for, all of a sudden, a dam had burst–alas! Notwithstanding, I got there. The house is tiny, with a straw-thatched roof. The windows are illuminated: which signifies, that they are expecting me. An old woman comes out to receive me,–such a dignified old woman, in a mob-cap; ‘Save her,’ says she, ‘she is dying.’ ‘Pray don’t worry,’ I say to her. . . . . . . .’Where is the patient?’–‘Here, please come this way.’–I look: ’tis a neat little room, in the corner a shrine-lamp, on the bed a girl of twenty years, unconscious. She is fairly burning with heat, she breathes heavily:–’tis fever. There are two other young girls present, her sisters,–thoroughly frightened, in tears.–‘See there,’ say they, ‘yesterday she was perfectly well, and ate with appetite: this morning she complained of her head, and toward evening, all of a sudden, she got into this condition.’ . . . . I said again: ‘Pray don’t worry,’–you know, the doctor is bound to say that, — and set to work. I let blood, ordered the application of mustard-plasters, prescribed a potion. In the meantime, I looked and looked at her, and do you know:–well, upon my word, I never before had seen such a face . . . .. a beauty, in one word! I fairly go to pieces with compassion. Such pleasing features, eyes. . . . . . Well, thank God, she quieted down; the perspiration broke out, she seemed to regain consciousness, cast a glance around her, smiled, passed her hand over her face. . . . Her sisters bent over her, and inquired: ‘What ails thee?’–‘Nothing,’–says she, and turned away . . . . . . I look . . and lo, she has fallen asleep. ‘Well,’ I say, ‘now the patient must be left in peace.’ So we all went out of the room on tiptoe; only the maid remained, in case she should be needed. And in the drawing-room, the samovar was already standing on the table, and there was Jamaica rum also: in our business, we cannot get along without it. They gave me tea, and begged me to spend the night there. . . . I consented: what was the use of going away now! The old woman kept moaning. ‘What’s the matter with you?’ said I: ‘she’ll live, pray do not feel uneasy, and the best thing you can do is to get some rest yourself: it’s two o’clock.’–‘But will you give orders that I am to be awakened, if anything should happen?’–‘I will, I will.’–The old woman went off, and the girls also betook themselves to their own room; they made up a bed for me in the drawing-room. So I lay down,–but I couldn’t get to sleep,–and no wonder! I seemed to be fretting over something. I couldn’t get my sick girl out of my mind. At last, I could endure it no longer, and all of a sudden, I got up: I thought: ‘I’ll go and see how the patient is getting along.’ Her bedroom adjoined the drawing-room. Well, I rose, and opened the door softly,–and my heart began to beat violently. I took a look: the maid was fast asleep, with her mouth open, and even snoring, the beast! and the sick girl was lying with her face toward me, and throwing her arms about, the poor thing! I went up to her. . . All of a sudden, she opened her eyes, and fixed them on me! . . . . . ‘Who is this? Who is this?’–I was disconcerted.–‘Don’t be alarmed, madam,’ said I: ‘I’m the doctor, I have come to see how you are feeling.’–‘You are the doctor?’–‘Yes, the doctor. . . . . Your mamma sent to the town for me; we have bled you, madam; now, please to lie quiet, and in a couple of days, God willing, we’ll have you on your feet again.’–‘Akh, yes, yes, doctor, don’t let me die . . . . please, please don’t!’–‘What makes you say that, God bless you!’–‘Her fever is starting up again,’ I thought to myself. I felt her pulse: it was the fever, sure enough. She looked at me,–then, all of a sudden, she seized my hand.–‘I’ll tell you why I don’t want to die, I’ll tell you, I’ll tell you . . . . now we are alone; only, if you please, you mustn’t let anybody know . . . . listen!’ . . . . I bent down; she brought her lips to my very ear, her hair swept my cheek,–I confess that my head reeled, –and began to whisper. . . . . . I could understand nothing. . . .. . . Akh, why, she was delirious. . . . . She whispered and whispered, and very rapidly at that, and not in Russian, finished, shuddered, dropped her head back on the pillow, and menaced me with her finger.–‘See that you tell no one, doctor.’ . . . Somehow or other, I contrived to soothe her, gave her a drink, waked up the maid, and left the room.”

Here the doctor took snuff frantically, and grew torpid for a moment.

“But, contrary to my expectation,”–he went on,–“the patient was no better on the following day. I cogitated, and cogitated, and all of a sudden, I decided to remain, although other patients were expecting me. . . .. But, you know, that cannot be neglected: your practice suffers from it. But, in the first place, the sick girl was, really, in a desperate condition; and, in the second place, I must tell the truth, I felt strongly attracted to her. Moreover, the whole family pleased me. Although they were not wealthy people, yet their culture was, I may say, rare. . . . . Their father had been a learned man, a writer; he had died in poverty, of course, but had managed to impart a splendid education to his children; he had also left behind him many books. Whether it was because I worked so zealously over the sick girl, or for other reasons, at all events, I venture to assert that they became as fond of me as though I had been a relative . . . .. . In the meantime, the thaw had reduced the roads to a frightful condition: all communications were, so to speak, utterly cut off . . . . The sick girl did not get well . . . day after day, day after day. . . . But so, sir . . . . then, sir . . . .” (The doctor paused for a while).–“Really, I do not know how to state it to you, sir . . .” (Again he took snuff, grunted, and swallowed a mouthful of tea.) “I will tell you, without circumlocution,–my patient . . . . anyhow . . . . well, either she fell in love with me . . . . . or, no, she didn’t exactly fall in love with me . .. . but, anyway . . . really, how shall I put it? . . .” (The doctor dropped his eyes, and flushed crimson.)

“No,”–he went on with vivacity:–” she didn’t fall in love with me! One must, after all, estimate one’s self at one’s true value. She was a cultivated girl, clever, well-read, and I had forgotten even my Latin, completely, I may say. So far as my figure is concerned” (the doctor surveyed himself with a smile), “also, I have nothing to boast of, apparently. But the Lord God didn’t distort me into a fool, either: I won’t call white black; I understand a thing or two myself. For example, I understood very well indeed that Alexandra Andreevna– her name was Alexandra Andreevna–did not feel love for me, but, so to speak, a friendly inclination, respect, something of that sort. Although she herself, possibly, was mistaken on that point, yet her condition was such, as you can judge for yourself . . . . . However,”–added the doctor, who had uttered all these disjointed speeches without stopping to take breath, and with obvious embarrassment:–” I have strayed from the subject a bit, I think. . . . So you will not understand anything . . . . . but here now, with your permission, I’ll tell you the whole story in due order.”

He finished his glass of tea, and began to talk in a more composed voice.

“Well, then, to proceed, sir. My patient grew constantly worse, and worse, and worse. You are not a medical man, my dear sir; you cannot comprehend what takes place in the soul of a fellow-being, especially when he first begins to divine that his malady is conquering him. What becomes of his self-confidence! All of a sudden, you grow inexpressibly timid. It seems to you, that you have forgotten everything you ever knew, and that the patient does not trust you and that others are beginning to observe that you have lost your wits, and communicate the symptoms to you unwillingly, gaze askance at you, whisper together . . . . . . eh, ’tis an evil plight! But there certainly must be a remedy for this malady, you think, if you could only find it. Here now, isn’t this it? You try it–no that’s not it! You don’t give the medicine time to act properly . . . . now you grasp at this, now at that. You take your prescription-book, –it certainly must be there, you think. To tell the truth, you sometimes open it at haphazard: perchance Fate, you think to yourself . . . . . But, in the meanwhile, the person is dying; and some other physician might have saved him. A consultation is necessary, you say: ‘I will not assume the responsibility.’ And what a fool you seem under such circumstances! Well, and you’ll learn to bear it patiently, in course of time you won’t mind it. The man dies–it is no fault of yours: you have followed the rules. But there’s another torturing thing about it: you behold blind confidence in you, and you yourself feel that you are not capable of helping. Well then, that was precisely the sort of confidence that Alexandra Andreevna’s whole family had in me:–and they forgot to think that their daughter was in danger. I, also, on my side, assured them that it was all right, while my soul sank into my heels. To crown the calamity, the thaw and breaking up of the roads were so bad, that the coachman would travel whole days at a time in quest of medicine. And I never left the sick-chamber, I couldn’t tear myself away, you know, I related ridiculous little anecdotes, and played cards with her. I sat up all night. My old woman thanked me with tears; but I thought to myself: ‘I don’t deserve your gratitude.’ I will confess to you frankly,–there’s no reason why I should dissimulate now,–I had fallen in love with my patient. And Alexandra Andreevna had become attached to me: she would let no one but me enter the room. She would begin to chat with me, and would interrogate me–where I had studied, how I lived, who were my parents, whom did I visit? And I felt that she ought not to talk, but as for prohibiting her, positively, you know, I couldn’t do it. I would clutch my head:–‘What art thou doing, thou villain?’–But then, she would take my hand, and hold it, and gaze at me, gaze long, very long, turn away, sigh, and say: ‘How kind you are!’ Her hands were so hot, her eyes were big and languishing.–‘Yes,’ she would say,–‘you are a good man, you are not like our neighbours. . . . no, you are not that sort. . . . How is it that I have never known you until now!’ –‘Calm yourself, Alexandra Andreevna,’–I would say. . . . ‘I assure you, I feel I do not know how I have merited . . . . only, compose yourself, for God’s sake . . . . everything will be all right, you will get well.’–And yet, I must confess to you,” added the doctor, bending forward, and elevating his eyebrows:–“that they had very little to do with the neighbours, because the lower sort were not their equals, and pride prevented their becoming acquainted with the rich ones. As I have told you, it was an extremely cultured family:–and, so, you know, I felt flattered. She would take her medicine from no hands but mine . . . she would sit up half-way, the poor girl, with my assistance, take it, and look at me . . . . and my heart would fairly throb. But, in the meantime, she grew worse and worse: ‘She will die,’ I thought, ‘she will infallibly die.’ Will you believe it, I felt like lying down in the grave myself: but her mother and sisters were watching, and looking me in the eye . . . . and their confidence disappeared.

“‘What is it? What is the matter?’–‘Nothing, ma’am; ’tis all right, ma’am!’–but it wasn’t all right, I had merely lost my head! Well, sir, one night I was sitting alone once more, beside the sick girl. The maid was sitting in the room also, and snoring with all her might. . . . Well, there was no use in being hard on the unfortunate maid: she was harassed enough. Alexandra Andreevna had been feeling very badly all the evening; she was tortured by the fever. She kept tossing herself about clear up to midnight; at last, she seemed to fall asleep; at all events, she did not stir, but lay quietly. The shrine-lamp was burning in front of the holy picture in the corner. I was sitting, you know, with drooping head, and dozing also. All of a sudden, I felt exactly as though some one had nudged me in the ribs. I turned round. . . O Lord, my God! Alexandra Andreevna was staring at me with all her eyes . . . her lips parted, her cheeks fairly blazing. — ‘What is the matter with you?’–‘Doctor, surely I am dying?’–‘God forbid!’–‘No, doctor, no; please don’t tell me that I shall recover . . .. . don’t tell me . . . if you only knew . . . listen, for God’s sake, don’t conceal my condition from me!’–and she breathed very fast.–‘If I know for certain that I must die . . . . I will tell you everything, everything!’–‘For heaven’s sake, Alexandra Andreevna!’–‘Listen, I haven’t been asleep at all, you see; I’ve been watching you this long while. . . . for God’s sake . . . I believe in you, you are a kind man, you are an honest man; I adjure you, by all that is holy on earth–tell me the truth! If you only knew how important it is to me. . . Doctor, tell me, for God’s sake, am I in danger?’–‘What shall I say to you, Alexandra Andreevna, for mercy’s sake!’–‘For God’s sake, I beseech you!’–‘I cannot conceal from you, Alexandra Andreevna, the fact that you really are in danger, but God is merciful . . . .’–‘I shall die, I shall die!’ . . .. . And she seemed to be glad, her face became so cheerful; I was frightened.–‘But don’t be afraid, don’t be afraid, death does not terrify me in the least.’–All of a sudden, she raised herself up and propped herself on her elbow.–‘Now . . . . well, now I can tell you that I am grateful to you with all my soul, that you are a kind, good man, that I love you.’ . . . . I stared at her like a crazy man; dread fell upon me, you know. . . ‘Do you hear?–I love you!’ . . . . ‘Alexandra Andreevna, how have I deserved this!’–‘No no, you don’t understand me . . . . thou dost not understand me.’ . . . . And all of a sudden, she stretched out her arms, clasped my head, and kissed me. . . . Will you believe it, I came near shrieking aloud . . . . . I flung myself on my knees, and hid my head in the pillow. She was silent; her fingers trembled on my hair; I heard her weeping. I began to comfort her, to reassure her . . . . to tell the truth, I really do not know what I said to her.–‘You will waken the maid, Alexandra Andreevna,’ I said to her. . . ‘I thank you . . . . believe me . .. . . calm yourself.’–‘Yes, enough, enough,’ she repeated. ‘God be with them all; well, they will wake; well, they will come–it makes no difference: for I shall die. . . . . But why art thou timid, what dost thou fear? raise thy head. . . . Can it be myself? . . . . in that case, forgive me,’–‘Alexandra Andreevna, what are you saying? . . . . I love you, Alexandra Andreevna.’–She looked me straight in the eye, and opened her arms.–‘Then embrace me.’ . . I will tell you frankly: I don’t understand why I did not go crazy that night. I was conscious that my patient was killing herself; I saw that she was not quite clear in her head; I understood, also, that had she not thought herself on the brink of death, she would not have thought of me; for, you may say what you like, ’tis a terrible thing, all the same, to die at the age of twenty, without having loved any one: that is what was tormenting her, you see; that is why she, in her despair, clutched even at me,–do you understand now? But she did not release me from her arms.–‘Spare me, Alexandra Andreevna, and spare yourself also,’ I said.–‘Why should I?’ she said. ‘For I must die, you know.’ . . . She kept repeating this incessantly.–‘See here, now; if I knew that I would recover, and become an honest young lady again, I should be ashamed, actually ashamed . . . . but as it is, what does it matter?’–‘But who told you that you were going to die?’–‘Eh, no, enough of that, thou canst not deceive me, thou dost not know how to lie; look at thyself.’–‘You will live, Alexandra Andreevna; I will cure you. We will ask your mother’s blessing on our marriage. . . . We will unite ourselves in the bonds. . . We shall be happy.’–‘No, no, I have taken your word for it, I must die . . . . thou hast promised me . . . thou hast told me so.’ . . . This was bitter to me, bitter for many reasons. And you can judge for yourself, what trifling things happen: they seem to be nothing, yet they hurt. She took it into her head to ask me what my name was,–not my surname, but my baptismal name. My ill-luck decreed that it should be Trifon. Yes, sir, yes, sir; Trifon, Trifon Ivanovitch. Everybody in the house addressed me as doctor. There was no help for it, I said: ‘Trifon, madam.’ She narrowed her eyes, shook her head, and whispered something in French,–okh, yes, and it was something bad, and then she laughed, and in an ugly way too. Well, and I spent the greater part of the night with her in that manner. In the morning, I left the room, as though I had been a madman; I went into her room again by daylight, after tea. My God, my God! She was unrecognisable: corpses have more colour when they are laid in their coffins. I swear to you, by my honour, I do not understand now, I positively do not understand, how I survived that torture. Three days, three nights more did my patient linger on . . . . and what nights they were! What was there that she did not say to me! . . . . And, on the last night, just imagine,–I was sitting beside her, and beseeching one thing only of God: ‘Take her to Thyself, as speedily as may be, and me along with her.’ . . . All of a sudden, the old mother bursts into the room . . . . . I had already told her, on the preceding day, that there was but little hope, that the girl was in a bad way, and that it would not be out of place to send for the priest. As soon as the sick girl beheld her mother, she said:–‘Well, now, ‘t is a good thing thou hast come . . . look at us, we love each other, we have given each other our promise.’–‘What does she mean, doctor, what does she mean?’–I turned deathly pale.–‘She’s delirious, ma’am,’ said I; ”tis the fever heat.’ . . But the girl said: ‘Enough of that, enough of that, thou hast just said something entirely different to me, and hast accepted a ring from me. Why dost thou dissimulate? My mother is kind, she will forgive, she will understand; but I am dying–I have no object in lying; give me thy hand.’ . . . . I sprang up and fled from the room. The old woman, of course, guessed how things stood.

“But I will not weary you, and I must admit that it is painful to me to recall all this. My patient died on the following day. The kingdom of heaven be hers!” added the doctor hastily, with a sigh. “Before she died, she asked her family to leave the room, and leave me alone with her.–‘Forgive me,’–she said,–‘perhaps I am culpable in your sight . . . . .. my illness . . . but, believe me, I have never loved any one more than I have loved you . . . . do not forget me . . . . take care of my ring. . . . .. .'”

The doctor turned away; I took his hand.

“Ekh,”–he said,–“let’s talk of something else, or wouldn’t you like to play preference for a while? Men like us, you know, ought not to yield to such lofty sentiments. All we fellows have to think of is: how to keep the children from squalling, and our wives from scolding. For since then, you see, I have managed to contract a legal marriage, as the saying is. . . Of course . . . . I took a merchant’s daughter: she had seven thousand rubles of dowry. Her name is Akulina; just a match for Trifon. She’s a vixen, I must tell you; but, luckily, she sleeps all day. . . But how about that game of preference?”

We sat down to play preference, for kopek stakes. Trifon Ivanitch won two rubles and a half from me–and went away late, greatly elated with his victory.

[Every month, The Reading Room showcases a short story, or excerpts of a book, from some of the greatest writers the world has ever seen. This month’s selection is Ivan S. Turgenev’s The District Doctor.]