Interview with Kyle Kouri

I took a piss about a month ago and I remembered art. It was in a bar bathroom just north of Houston on Ave A. The bar is called the Library and I went there because everyone raves about the jukebox (it was good) and the bartenders (they were hot). But these things are not uncommon among haunts down the lower east side. It wasn’t until I went to exit the bathroom that things got interesting.

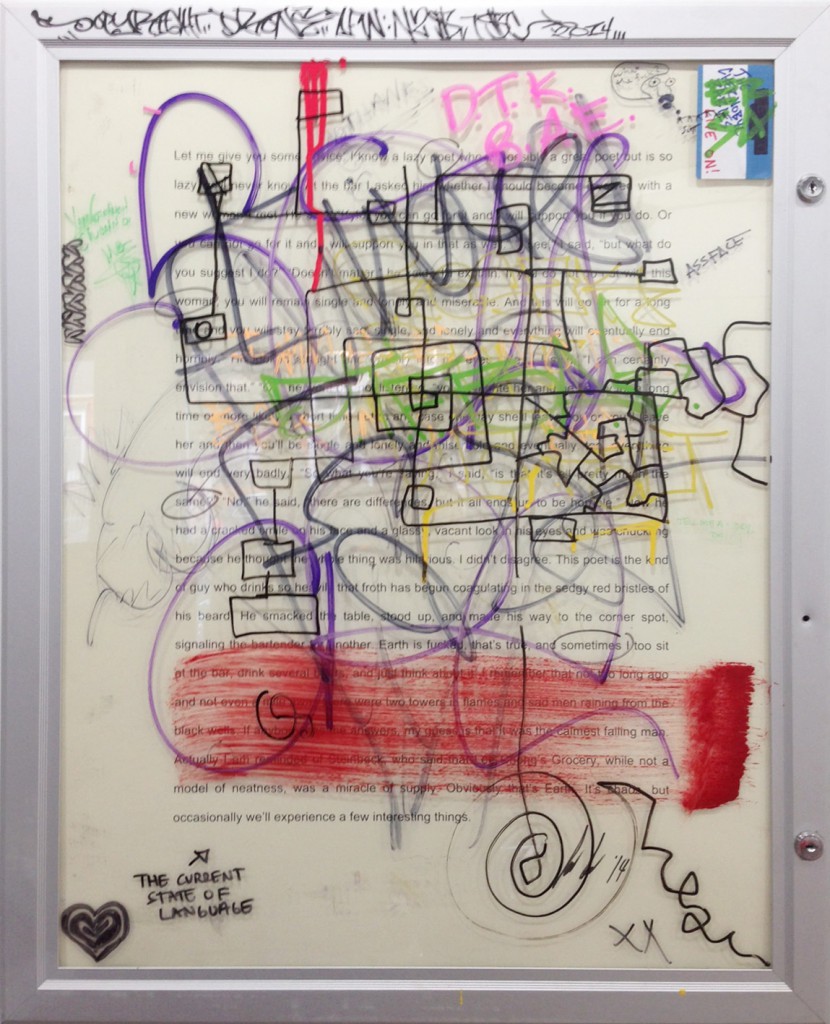

Framed, under a disgusting display of graffiti and airborne grime, was a short story hanging on the bathroom door. One page of text, about a size 20 font, telling some sort of story. I could only read about half of it under the bathroom muck, but it was cool. One of those ideas that seems so simple, yet the result is something everyone is after. The facade was like an interactive canvas. Those who came before had drawn pictures of ants, left their tags, and continued sentences in magic marker.

At the bar I asked what the deal was. The bartender pointed at a dude with cool hair and a Germs shirt drinking a glass of white wine. “He’s the artist,” she said, “ask him.” He looked at me, but he didn’t smile. I introduced myself as a writer for a British art magazine, which garners credibility among strangers in certain circles. He said his name was Kyle Kouri. For the rest of the night we drank, smoked, and in-between, discussed his art.

I learned that the Library was one of several bars that housed Kouri’s “work.” But I didn’t learn about his process until a week later when we met again at his apartment. Kouri is a resident of the lower east side. In his lobby I pointed at a copy of the New York Times and mentioned how I steal my neighbor’s every morning. He said he used to do the same but gestured at a sign that said if you can afford to live in this building you can afford to buy your own newspaper. “They watch now,” he said.

Kouri lives in a studio apartment with a bookcase full of titles that range from what he says is “the best thing ever written” to “complete shit. But the guy who wrote it is my friend.” Kyle’s own stories were sitting around the apartment, in various stages of completion. Some were framed, some were written in pen on cardboard pizza boxes and waiter’s checkbooks.

I looked at the framed stuff. Under apartment light. So neat and clean. I thought about how nothing is just birthed as the object we see. And even though the mutation of Kouri’s art happens in the bathroom of a dive bar, it begins in a controlled environment. Days to weeks are spent writing and rewriting these one or two page stories before they are framed and displayed. But these are days and weeks spent alone, with fuel from booze to speed to hungover revision to cigarettes to fear and paranoia and finally acceptance.

The frame taunts the vandals. And just before it becomes camouflaged in the stylized mess of all LES bathroom walls, it’s removed. There’s no set duration. Maybe a week. Maybe a month. Maybe after Kyle has drunk enough pints and gets tired of looking at his creation as he pisses them out. Usually they go from bathroom to gallery, but Kyle’s most recent showing is something different.

Titled OFFICE PARTY, the viewer is led through two floors of gallery space to the single bathroom. Inside Kouri has set up his show as an installation. Anyone who has ever been a corporate slave will notice some familiar paraphernalia. A bland tie, reminiscent of a uniform you might be handed as you clock in and return again while clocking out, is flopped out from under the toilet lid. As if someone had enough and tried to flush their chains away. Or better, they’d jumped in and drowned themselves.

If no one is using the toilet, standing in the door frame is the best way to take in the room. From there you can view the two works hanging on the wall. Both of an office. Both with dialogue rife with exploitation and futility. Under the sink is a tattered copy of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and The Dead. The first sentence is underlined: Nobody could sleep. When someone does have to go, the tool box propping open the door must be removed. In it perfectly fits Olde English 40s like eggs in a carton. Cigarettes line the pockets and a pink butt plug rises from the box like a happy plant. The name of this piece: Men At Work.

Kyle’s work has cultivated a devoted following. I ask him about being twenty-four and generating money as an artist. He says, “It’s dope.”

Interview conducted in the lobby of the Bowery Hotel.

You’re referred to as an “artist”, what do you consider yourself?

My first month in college I began writing a horror novel called Bill Quigly and finished it Halloween night on Adderall, in a private study room, keeping one eye on an Olde English 40 that was close by. The book received a lot of positive acclaim from my teachers and peers, at which point I got an ego. I wrote, took drugs, and drank away that year, same one my dad died, and completed several more works that I still consider very good. They had the magic of a young artist on a roll for the very first time. I also fell in love with a rock and roller and we had a ball terrorizing people as often as we liked. Many times we pretended to be physically abusive towards each other and I’d slap her in front of horrified, virgin eyes.

Sophomore year I became a black square and a paranoid. I studied Russian history and wore a hoodie that I had sewn a fox head to. I wrote one good story called “Troubled Stars,” but the rest was forced and ultimately for the trash bin. Then I had a breakdown and became a Christian—Andrew Thurman and I wore crosses and prayed at night drunk and on drugs in December. But the magic came back in a sort of parodied, self-aware and ironic way my Spring semester when I wrote a story called “God Shines Brightest on the Highest Man,” which concerned a deranged college student who thought he was a professional writer and handed out his stories all over campus, urging people to read. This is probably my first performance because I actually walked around school for days, giving out the piece to everybody.

After that I joined the basketball team, cut back on drugs and alcohol, and became a real boring, confused, straighto that did his homework and believed. My senior year I brought out my knife at parties but it was a poor comeback, dull mimicry compared to the real freak punk I had been. Nick and I were captains, understand, and had responsibilities to our team. I did, however, write some essays for a website called SLC Speaks and The Faster Times which are not good but you can probably find those online.

Then I graduated and moved to New York, where a friend of mine was selling paintings. I had a little extra money so I started buying work, mainly because my father had been an art collector, and also too because Max, the art dealer, led me to believe it was the thing. Buy art. Anyway I got to know the artists and I think right away a small part of me started feeling that their lives were the kind of lives to live. These guys are older than me and I admired them a lot. Eventually I couldn’t afford artwork anymore so I started writing about it, and the boys knew me as the guy who wrote about their paintings. But writing about art is probably the most boring, stupid thing I can imagine doing so I stopped, and became enamored with Max’s life, convincing him to let me start selling paintings instead. I was good at it too and made some money doing that. But ultimately that was a big performance as well. I knew I’d never be an art dealer, only enjoyed perfecting the role. I mastered the eyebrows, smirk, handshake and nasal, drawling talk. The seductive and aggressive game of selling pictures. The whole thing was hilarious to me and when I think about it now it’s actually amazing that I was able to trick so many people into spending all this money because I told them to, when I hadn’t even studied art in school.

But it wasn’t fulfilling and I had all these paintings hanging, leaning, lying in my apartment and all I could think about is what I’d like to do instead. So it struck me one day after Max and I had curated a show featuring my writing and Sam Stabler and William Buchina’s paintings that I ought to drop the bullshit and start making work myself. Which I did. And with only one series completed, featuring stories screen printed on paper, framed in black, I convinced Max to start putting my work in shows. Now I’ve made many things, including painting, sculpture, installation work, and more stories, and people refer to me as an artist. I refer to myself as an artist too, but mainly I just think that I’m a punk rock and roller and a real bad dude.

Self Portrait (Because it’s horrible)

What is human?

I was talking to Mike Alongi, the photographer, on the graveyard shift at the hotel where we work. We came around to discussing a very real fear the both of us share about selling our souls. Now I asked Michael if he ever got the feeling that he had already sold his and he said, “No, but in dreams I’ve gotten close.” And I told him that on a few occasions I’ve felt that mine might actually be gone. For instance one day during work I went to piss and while washing my hands, gazing in the mirror, I had the strangest feeling that I was damned, and my memory had just been wiped clean of the grey day I shook the Devil’s Hand. Now in that moment I couldn’t see the sparkle in my pupils that generally appears during the laugh after a good joke or when you’re in the fit of a fine idea or falling in love after a long while of loss and regret. Since then I think the light has come back but I can’t actually say for sure on account of I’ve been working like a dog, either on Office Party, my show, or at the hotel, which hasn’t left a lot of time for personal reflection. Or sleep. But I will say that whatever’s at the heart of us, and maybe it’s only dirt, there does exist a bird that visits me from time to time—and the bird herself could be a trick too—but in any case she’s a good trick, and I’d really not like to lose her.

Happiness?

You know I visited this girl I like at her job before I had to go my own way for an overnight shift. She was bartending at a shithole comedy joint but it was empty the way I like ‘em and when I arrived she smiled, mysteriously, wearing this amazing red shirt, and suddenly I felt at home. I sat down and had a few quick ones. She joined me in between orders and her nearby presence alone was enough to make me seize and scream. Even better outside I had a cigarette while she smoked weed and after, in the half second between goodbye and literal, parting footsteps, we kissed once, another time, and separated now into a new world. In that open, glowing space I felt untoward joy. My mind was gunfire; sex and tears. I was so happy I could have thrown myself in front of a speeding taxicab and nearly did, except it was an Uber, and the driver slowed down and swerved, suspecting my irrational game. But as it goes I soon got to work, felt the creeping hangover, was unsure if my body was begging to piss or shit itself, or whether I simply needed to throw-up from overdosed excitement.

Or neither, just stay still.

Darkness?

A friend and I are a part of a two man troupe called Strange White Folk, in which we write suicide raps, mainly taking ourselves through verse into the darkest places we can conjure. My name is Big Murder and his is Ole Pussytoe. This exploration has been going on for some time now, about two years, mainly via email. We’re not at the bottom yet, but I’ll share a few bars of mine that may illustrate accurately my feelings on that word:

Touched young by the darkness

bad habit where I fart shits

my fate is fiendishly mark-ed

bound to be a self-wrought carcass

First on no one at all’s list

except for my personal deathwish

Long bearded thoughts get my gist?

save the razor blade for my thin fag wrists

Hated by all of my past cliques

Whatevs they can suck horse dick

plus never been a big fan of friendship

Hammer my own hands look at the breadsticks

All alone ‘cept when fucking fat chicks

Then more alone I am so ratchet

Did I say rachet? I meant fucking ratshit

It’s the dead rat up the fat chick’s ass trick

And:

Ya’ll know, still hate on shit like friendship

In BK, cop feels of black dudes with the big dicks

What the fuck, it’s not what, alone on the deathship

Calm waters: black waves say Murder’s not it

On the street, forgot how to walk though

I hate the universe, but I hate the Earth mo’

Bar bathrooms, respect, still my dojo

RALPH, with the piss on the polo

Egg Whites, keep that shit in my closet

After a month, white yellow becomes mosses

Eat it up, no hesitation or pauses

I’m an idiot. Food poisoning is awesome

Was there ever a point, like when you were young, that you found another artist and said, “That’s what I want to do”?

Yeah man I’ve always wanted to be like Johnny Cash and Jack Nicholson. Still do. These days I also really admire Paul McCarthy, Richard Prince, Lars von Trier, John Carpenter, Henry Miller, and adore every novel by Michel Houellebecq.

Incidentally I have mixed feelings about On The Road. But in any case, if Jack and his boys represent the mad angels on America’s right shoulder, I am the inspired devil on the left side.

–Also I hate groups.

What parts of yourself don’t you share?

My friends know that I become paranoid to the brink of madness over the most pointless and bizarre things. One day I ate a fishstick despite noticing a slight tear in the packaging and got quiet afterwards, curled up in a corner, coldsweating, grinding my teeth in a fit of lunatic unease. F Scott pale I admitted to Matt Alberswerth my fears. “Albers,” I said, “you don’t think I’ve been poisoned, do you? Or dosed with LSD?”

Matt in general reasons with me like a girlfriend or mother would, and this time soothed me back to sane. “Well, huh. Kyle, I’ll tell you what. I’d say that’s unlikely.” Andrew is something else:

“You’re a sick individual. You have a disease.” Which might be true.

What is your ideal situation to create in?

(refer to question 8)

Where do you see your art taking us?

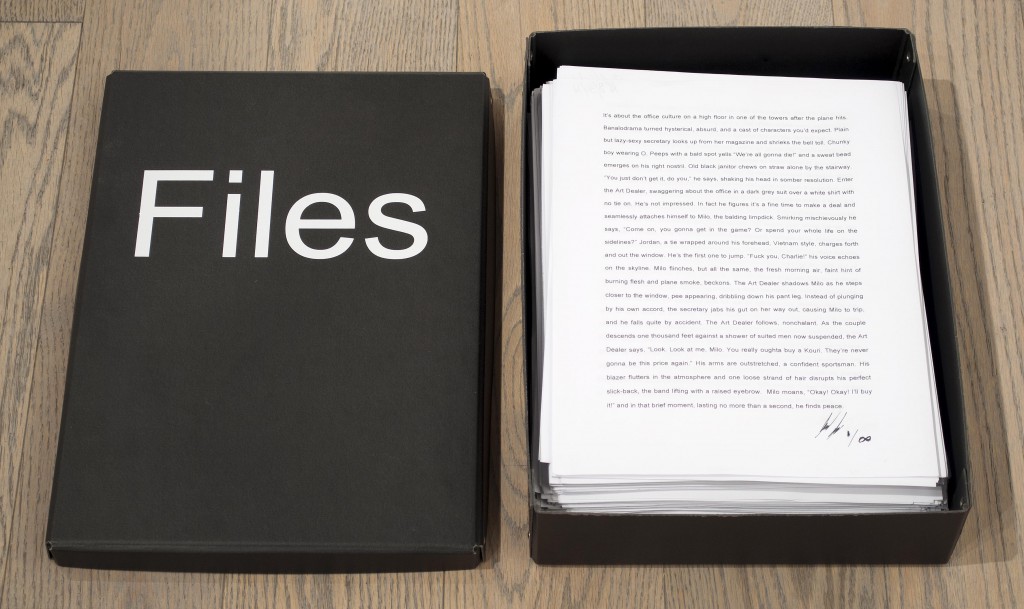

Hopefully to your wallet, man. This day job is making me mad. For instance in my most recent show, Office Party, there is a sculpture called “Files.” Now this piece consists of eight bland, black boxes I bought at The Container Store. On top of each I vinyled the word “Files” and once “Flies” because at the office there’s always mistakes. And flies. In each box there are 500 copies of the same one page story, dated, initialed, signed, and editioned to infinity. Now the idea here was to sign myself up for an eternity of busywork. See I’ll always be signing files now until I die. So far I’ve gotten to 4,167, which is pretty good, considering I did that in a week, at the hotel or all alone in a corner of Garis & Hahn Gallery.

And that’s the thing about my day job. I check-in the Eurotrash, direct them to the disco, kindly explain to the same garbage five minutes later why they can’t get into the disco, make keycard booklets, radio the engineers about the shit spewing out of toilets, call the housekeepers about the bugs, sort the registration cards for accounting, replenish the pencil and paper supplies for my colleagues, deliver packages to the French, pick-up laundry from the Brazilians, request dental kits for New Jersey, kill mosquitos with Aaron, charge the drug dealer’s phone, calm down the prostitutes, nod in feigned sympathy to every hungover john that got robbed, all at the same time, while simultaneously trying to sign my files. Which is hilarious because the files I decided to do myself.

Who would you like to wake up with a new album from (assuming you think U2 is terrible)?

Look man. I’ve read enough Gothic literature to know that you don’t want to fool around with raising the dead. And generally speaking people do what they gotta do, or don’t, but in any case they die. It’s no use dreaming about making it any other way. But having said that, if I had to answer your question there’s only one answer I would give: On The Run. That was my band during high school. I was lead singer and guitarist and once played an entire show wearing a sexy cop dress, high as a drone off rum and Robitussin, and sang a country song about giving blowjobs to my friends.

What will your epitaph say?

My name. A crooked cross on top the tombstone. The text faded over the years, in time an anonymous grave.