Backyard Film Festival

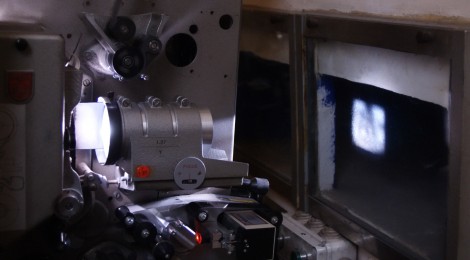

When Fred Schneider turned sixty, he wanted to mark the occasion. A tall, thin man with reddish blond hair, he describes the feeling as a delayed midlife crisis. But instead of buying a sports car or taking a mistress, he bought a digital movie projector, an Epson Movie Mate 60, which plays DVDs.

The projector formed part of a plan. That same year saw the first Backyard Film Festival, held during the summer of 2011. On ten Saturday nights, Schneider and his wife Irene Dorrier invited friends and neighbors to watch a movie in their backyard. They rented movies from Netflix, hung a roll-down screen from a pergola, provided citronella candles to ward off bugs, and had a few extra folding chairs on hand.

The event was enough of a success that they repeated it. The fourth annual Backyard Film Festival took place this summer on a compressed schedule, five weekends of films shown Friday and Saturday during August. This schedule allowed Schneider and Dorrier to make a road trip in June and July, from their home in Charlottesville, Virginia to Yellowstone National Park.

In addition to natural wonders, they took in Midwestern buildings by famous American architects Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. Schneider is an architect by training, now active as a volunteer for the city electoral board as a voting machine technician. Dorrier is a former art teacher in elementary schools.

Each year, the Backyard Film Festival has a theme and a poster, designed and printed by Schneider. In 2012, the theme was “Southern Stories, Southern Secrets,” with films like Alabama Moon, Gone With the Wind and Fried Green Tomatoes. This year, the theme was “The Sixties,” with films selected from the 1960s. A Hard Day’s Night, featuring the Beatles, was the biggest draw. Also shown were Dr. No, Cat Ballou, The Graduate, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. To quote from Schneider’s poster, “Has it been fifty years already since the greatest decade of our lives? Here are some movies that in many ways helped define the decade and influenced much that has come since.”

From an email list of about 80 names, anywhere from two to twenty show up, Schneider says. He gives a brief verbal introduction to each film, and he invites people to linger afterward for discussion. Optional donations go to a different charity each year. In 2011, it was Habitat for Humanity, which builds housing for low-income, first time buyers. This year, it was IMPACT, the Interfaith Movement Promoting Action by Congregations Together, a social justice group.

Rain has forced Schneider and Dorrier to move the show inside a few times. They hang the screen in an arch that opens to the dining room, and people fill the living room, sitting on the floor if necessary. Once, the projector quit a few minutes into the movie. Schneider was able to fix it by reading the owner’s manual. People bring snacks, and Dorrier has been known to serve ice cream.

Born in the Bronx and raised in Yonkers, New York, Schneider attended public schools, where “I was the geeky kid who operated the audio-visual equipment.” His first camera was a Kodak Instamatic, with which he took pictures of the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. After he graduated from college, in the summer of 1973, he and a friend drove through Europe, where Schneider took photos with a Nikon. Architecture school at the University of Virginia followed, with jobs in London and Charlottesville, where Schneider set up his own practice.

Photographing architecture has a good deal in common with shooting a film, Schneider says. Camera angle, lighting, and movement through space all contribute to a convincing image. So one of the things he looks for in choosing films is good photography. He is drawn to British films for their ensemble acting and for their sense of humor. Above all, he likes a good story. “I’m not much into horror films, psychological thrillers, car chases and explosions,” he says. For “The Sixties,” he gave Hitchcock’s classic film Psycho a pass for being “too violent.”

The Virginia Film Festival, now in its 27th year in Charlottesville, and sponsored by the University of Virginia, was an example, Schneider says. He enjoyed visits by the renowned critic Roger Ebert, especially Ebert’s detailed analysis of Blow-Up. Antonioni’s depiction of 1960s London and the Mod fashion scene made it to the backyard this year.

In fact, Schneider’s do-it-yourself festival grew out of a family ritual. During Sunday visits to his widowed father in Scottsville, Virginia, Schneider got in the habit of bringing a movie for them to watch together. When Bill Schneider, now age 96, moved to Our Lady of Peace in Charlottesville, a retirement home owned by the Catholic Diocese of Virginia, he and Fred invited other residents to the apartment. When Our Lady of Peace added a theater in 2013, they moved the Sunday screenings there.

The theater has a projector mounted on the ceiling, surround sound, 18 fixed theater-type seats, and space for a dozen stackable chairs plus wheelchairs. Sherry Beverage, Activities Director for Our Lady of Peace, also shows movies there on Tuesday and Saturday afternoons. “We show classics, new releases, and requests by residents,” she says. “I don’t approve the Sunday or the weekday list. The residents say they’re adults. They’ve seen and heard it all. If they don’t like a particular movie, they just get up and leave.”

The Sunday Film Series now attracts 20 to 25 people every Sunday night at 6:30. A series of films this spring starring the British actress Judi Dench was popular, including the 2012 comedy The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel and the 2013 drama Philomena. This fall, they are watching the “Best Movies of 2013.” “There is no formal discussion,” Schneider says, “but people share their personal histories, especially when the films deal with a time period they lived through.”

Schneider and Dorrier intend to keep hosting the backyard series for the foreseeable future. This low-budget gift to the neighborhood is something anyone can pull off, they say. And yet, on a summer night under the stars, with crickets chirping along with the soundtrack, a hint of magic hangs in the air.