Luis

We experienced our first hurricane in that house on Frangipani Street, and luckily, you were too little to remember any of it.

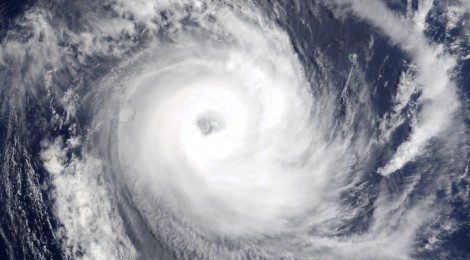

Hurricane Luis was a category five, like nothing that had ever hit us before—that’s what they said on the radio—with waves expected to reach up to thirty feet high. That’s how all the sand and the seaweed and the broken shells ended up in our yard and on our roof. Even in the trees, clinging to naked branches.

Papa hammered boards to the windows and the doors and we locked all six of the dogs inside with us. The smell of wet fur, thick in our nostrils, was nauseating. We sat in the living room eating dried sausage and canned peas, listening to the wind slapping the roof above us, bending the trees around us like zip wire. I sat cross-legged at Mama’s feet, Fidel’s head resting on my lap. Hours went by and we didn’t move, listening to the damage, praying the roof would still be on in the morning.

Occasionally, I peeked through the cracks in the windows, inhaling the smell of wet, upturned soil.

Mama had you bundled against her on the old couch, and every time I’d look, she’d be bouncing you on the edge of her knee, her lips pressed against the soft part of your head.

We slept on inflatable pool mattresses because our bed mattresses were propped between the wooden boards and the doors, to prevent banging. It still banged, all through the night, but Papa said it would’ve been much worse without them.

We walked in circles, restless, our palms pressed hard and flat against our eardrums. The whistling was unbearable. Papa said to imagine it was something else instead of the wind. The breeze down by the bay, he said, waves crashing beneath the water. I tried but couldn’t get the ringing out of my ears.

Even the dogs got tired of it. They howled back, scratched at the boards to get a better sniff of the air outside. It was hot out there, even with all that rain.

I stood barefoot on the shower tiles, peeking through the high window, through the plywood boards, mesmerized by the swaying of the trees, their trunks bowing to the ground. I wanted to go outside so badly, and the adrenaline made my heart thump wildly in my chest because I knew I would get blown away like a piece of sheet metal if I did.

Papa called me to the living room every now and then, telling me to stay away from glass windows.

I tucked a flashlight under my neck and read one book after another, the light wavering with every inhale, the inflatable mattress deflating slowly under me. Hurricanes were no fun, I decided. No fun at all.

Later that night, when the storm didn’t calm down but instead picked up speed, Mama pulled me into her lap. She was tapping her foot against the floorboards, worrying the dogs even more. They wouldn’t stop wincing.

“Guillaume,” she kept saying over and over again, “Oh, Guillaume…”

At the time, I didn’t know why she was repeating her brother’s name, swaying her body back and forth, mumbling his name into her chest like a prayer. I was more preoccupied with having to grab the Raisin Bran from the pantry. The window of the storeroom was the only window of the house that hadn’t been barricaded. Papa had run out of planks. Mama had stowed everything important in her bedroom closets, but had left behind a few things that would be easy to replace once the storm was over—cereal, powdered milk, pickle jars, pasta boxes. The glass expanded and contracted like breath, and I made the trip to the room as speedy as I could. I was terrified that the window would explode in thousands of pieces while I was in there, that shards of glass would fly into my eyes and I’d go blind forever.

Mama’s brother, Guillaume—Tonton, I called him—was a sailor. I’d heard stories about him. They were pretty much all I knew because he was never there, really, always sailing to an island or another, on a charter to the Grenadines or to the British Isles. My last memory of him was from that day we stopped by the pier before he sailed South to avoid the storm. The schooner stood tall and majestic, coated with black paint so shiny it hurt your eyes to stare at the hull for too long. It was just a tropical storm at that point, not the category five hurricane it turned into, almost overnight.

I remembered him standing proudly on the decks, his arms crossed tightly across his chest, his skin burned to a crisp by the sun. He didn’t look like Mama at all, I remembered thinking. Not like any of us.

Mama told me that once, at seventeen, he’d set their parents’ basement on fire and nearly died from his second and third degree burns. The doctors pretty much stitched his skin back on in pieces, she said. That’s why his skin looked like patchwork. It reminded me of snake skin because it shone in the light, and when you looked at it up close, you found intricate patterns under the tangled hairs of his arms.

“You know what he told the doctors?” Mama asked me, in her storytelling voice. “He said, don’t call my mother at work. Whatever you do, please don’t tell her what happened.”

Gran had a tendency to worry herself sick about things and Tonton knew that.

Mama was like her too. Every time I told her that, she’d laugh and say I would become like them too, when I had children someday.

At twenty-five, Tonton crossed the Atlantic Ocean by himself, with dreams of the Caribbean floating in his head. Alone, just him and the gulls circling the white masts. He was stubborn like that.

When he finally spotted land, after four weeks sailing the Atlantic, he’d been without food and water for almost two days. He told Mama he’d survived on spiced rum, and that he was seeing things, like krakens and mermaids and giant sea serpents swimming alongside the ship.

I liked to think all of it was real, not the consequence of dehydration and alcohol.

Now, at only twenty-nine, he was braving a category five hurricane on his ship, while we were tucked away behind planks and mattresses in our wooden bunker. My uncle was fearless. A true pirate.

He was the only reason I didn’t complain—not once—about my growling stomach or the ringing in my ears.

“He’s an idiot,” I heard Mama say to Papa. “He’d rather risk his life than abandon that stupid ship.” Then, she started crying.

It woke you up and you began to sob the way babies do, angry, wet, and scarlet red.

Shhhh baby, she said, and rocked you on her knee again. I wanted to be held close too.

I imagined Tonton, tall behind the ship’s helm, waves frothing above the decks, rain pouring down in gallons, wind slashing the masts. I didn’t understand the tragedy of it all at the time, how scared Mama was, how she kept dialing and redialing Gran’s number, though she knew the phone lines were dead. I didn’t realize, then, why Mama and Papa were sitting so close to the little staticky radio, Mama tapping her foot and Papa chewing his fingernails all the way to the bone.

Gran had refused to leave her house, terrified it would be pulled apart by the wind, that she would lose everything—her antique furniture, the leather-bound books, the china. It had happened to enough of our neighbors, our friends. Some of them had lost everything they owned in hurricanes, had been forced to dump it all because of the mildew growing on everything that had been soaked by the flood.

I’m sure she regretted it now, being all alone in that big old house. With the wind’s violent howling and the trees slashing each other outside. I knew I would be terrified, all alone in the dark. But Gran’s house was special to her—it was all she had—bought with her dead husband’s money–the grandfather I never met–and the little cash she’d collected from Chabanassy, the house she’d lived in with Mama before they traveled all the way to the Caribbean. But that’s another story.

Water kept gushing in through the cracks in the planks, flooding the living room. The pails that Papa had spread around the room were brimming with rainwater.

“Papa!” I kept saying. “Come help!”

When he didn’t budge I grabbed the rags in the kitchen and mopped the floors myself. That’s it, I kept thinking, the roof is going to blow off. I was convinced that I could hear the planks being ripped away, nails plucked out one by one by the wind.

The wind just kept getting stronger and stronger, no longer howling but screaming now. The dogs mimicked it, their yelps doubling in intensity and volume. I tried to shush them but they squealed even louder and after a while, I gave up trying. The water had reached the carpet now, and I tried to lift it off the ground, roll it to the side, but it was too heavy for me to lift alone.

“Papa!” I pleaded, but he just nodded, his eyes still fixed on the radio, his finger slowly turning the dial.

There was another wind gust and I could swear I felt the floorboards rise an inch off the earth. I covered my ears and pressed down as hard as I could, hoping it would make it stop.

Mama and Papa didn’t move, like they couldn’t hear any of it.