Camus’ Centenary: The Algerian Question

Camus associates a liberty in the rebellious act of choosing to live or die. However, this seems like a destitute version of liberty. When an individual has no say in his birth, choosing the “when” of death seems like an odd exercise of liberty. Death is the most certain and appointed fact of life. It is guaranteed by birth. Simply choosing the moment does not seem to constitute any significant form of rebellion. Nonetheless, Camus holds that we choose, and thereby exercise liberty through the very act of choosing life. For Camus, fundamental responsibility lies in passionate action to engage life for the sake of upholding universal values and heightening individual experience. In Yacine’s Algeria, death takes on a very different significance. He is not referring to a hypothetical and frivolous suicide caused by an intellectual crisis, one which bubbles across the surface of all of Camus’ writings. Camus discards the constant immediacy of death–suicide, for the experience of life. Yacine’s heroes, however, must embrace the constant immediacy of death–the likelihood of being killed, for the sake of their ideals.

Unlike Camus, Yacine presents a landscape where there is little liberty or choice, especially with regard to life and death. There is only the compulsion for freedom. He writes, “Lakdhar remembers, there were no more words now … No more talk, no more leaders, old rifles were spitting, far away the donkeys and mules were loyally leading our young army…. The whole village came to meet us, people had changed, they didn’t close the doors behind them anymore,” (74) There is no solitude, no isolation. There is no space for the luxury of alienation. There is only the struggle against the other. The other cannot be neglected in the pursuit of individual passion, because the other stands in the way of individualism itself.

Initially, Yacine places the reader in an environment seemingly without any moral restraint, where she is Witness to violence, sexual depravity, perversity, cowardice, and subjugation. There are no heroes in the beginning of this novel. Each character seems like a villain of sorts and we cannot help but judge them as such. We are a Camus-esque scenario, but we are witnessing it from the perspective of the victims of individual passion. We are reading Don Juan through the diary of a woman he left behind in his fast and furious pursuit of loves.

However, as the novel progresses, the reader learns about each man, about the path that led him to his own version of chaos. The reader begins to see how circumstances affected each one’s destinations. The final blow is delivered when Yacine reveals that the characters, assumed to be manual laborers, turn out to be young revolutionaries from elite backgrounds, rendered powerless by the colonial invasion. In this move, Yacine makes a strong claim: destitution can happen to anyone. With this last turn, he turns the story of Algeria into a story of humanity, human frailty and the descent of human character in the face of violence. This is what happened in Algeria, but if it happened anywhere else, individual destinies would remain unchanged.

The Man that Algeria Made

As in The Myth of Sisyphus, Yacine’s plot also suffers from a futile repetition. His circular plot ends exactly where it begins, in the same scene with the same conversation. The end of the narrative brings us back to the impossible possibility of recovery, the state of cautious optimism with which the book begins. Yacine seems to suggest that recovery is only possible through courage, yet courage in the face of violent and violently over-powering forces most likely means courage in the face of certain death.

What Camus and Yacine share in common is a similar experience of violence. However, what sets them apart is their position vis a vis the events. While Camus took shelter with the forces of subjugation, Yacine stood in the corner of the victims. In Yacine’s landscape, conscience is something that can be engaged. It is not completely lost. While in two hundred pages Yacine leaves us no further along in time from the first page, through a retelling of the narrative, he has transformed the readers perception of the facts. The reader understands that nothing was as it first seemed, neither the heroes, the landscape, nor the plot. This means that while actions are repetitive, adequate self-knowledge can provide a way out.

Camus’ heroes and his archetypes, on the other hand have no escape from their circular narratives. As Camus’ Absurd man runs away from his conscience, from his own measures and assessments of right and wrong and straight into the abyss of his passions, he runs aways from self-knowledge. As Camus denies any possibility of understanding the external world, he precludes external knowledge. By immersing himself in instant gratification, he rejects the possibility of improving his conditions. Ultimately, Camus surrenders to futility and escapes into delusion.

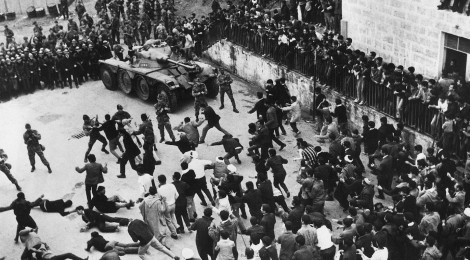

In Rebel, Albert Camus writes about the irrational courage of a man who launches himself towards an army to fight injustice. In context of the Algerian War of Independence, this statement develops an ironic weight. Yacine’s heroes understand this irrational courage and they embrace it as a kiss of death at the very moment that Camus deliberatively rejects suicide and embraces life without conscience or familiarity. Camus’ philosophy is a philosophy of alienation, futility, subjugation and incoherence. However, is it truly a philosophy of life? Or is it more simply a psychological portrait of the consequences of the loss of community and privilege?

Camus was a weak and marginalized member of an illegitimate community. As a Pied-Noirs, he was fighting a losing battle for the preservation of colonial structures that had seized to serve anyone other than colonial middle men. As an extension of the colonial regime, he was fighting despite the admitted brutality of the colonial administration. There was no courage in his cause. Worst of all, given the political tides of the hour, there was no hope either. With growing pangs of freedom, the small community of Pied-Noirs who had invaded Algeria in search of a better life were going to be forced to find a new home. This was inevitable. They had left their homes and built new communities in distant and dangerous lands. Like Sisyphus, laying the rock down on top of the hill after hours of struggle only to watch it roll down from where it came, the Pied-Noirs were now watching their efforts crumble to oblivion. Generations of struggle had proved futile. They would have to start all over again.

This very personal emblem of repetition in Camus’ own life provides deep resonance with the myth of Sisyphus and his request to imagine that Sisyphus was happy. However, this projection of contentment does nothing to change the conditions of Sisyphus’ destiny. It simply makes his life more tolerable and provides a false sense of power and control. Unlike the human agent, Sisyphus does not have the choice to commit suicide. Human beings do have this choice. If life is ultimately, as Camus’ theory implicitly admits a state of isolation and hopeless repetition, then his original question of whether one should choose life or death seems ultimately inadequately answered. In the context of his philosophy, Camus’ choice of life over death seems unclear.

Camus’ philosophy is ultimately a philosophy that emerges from trauma. The question that emerges is whether his frame is a result of universal observations or whether instead, Camus projected the futility of his own geo-political and social location on to the events of the world. While Camus provides important insight into the psychological consequences of colonialism, in the context of the brutality of the Algerian war, one is left wondering whether he provides any genuine insights to larger metaphysical problems. What we learn from Camus, therefore, is not a lesson about the world and its incoherence. Instead, what we take away is the psychological trauma of remaining silent in the face of known brutality.

Pages: 1 2