Proust and Art: Substance is Style

Style is not something extraneous to an artwork, but part of its essence: “A work of art only begins to exist from the moment that style appears.” – Proust, Marcel

In the critical evaluation of art (art in the general sense of the term, which includes all modes of creative and personal expression), are we to distinguish between form and content, style and substance, medium and message, or the object being represented and the means of representation? The more traditional view of Art has been that subject is supreme, either as a theological or religious motif, or as a crystallization of deep and intense feelings or as a portrayal of the exotic and picturesque in nature. Style here is incidental, somewhat peripheral to the subject, its only function being for aesthetic embellishment. The more modern notion ‘Art for Art’s sake’ on the other hand takes the direct opposite view. It seeks to eliminate the subject; it completely removes the question of meaning and purpose from the artwork. The whole value of the work is attributed to its form; it is discussed only in terms of style and technique – colour, shape, rhythm, composition. In either case style is divorced from the subject, and is not seen as something intrinsic to the work of art itself, intimately tied to the artist’s vision.

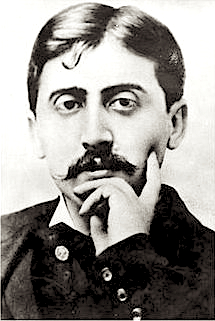

I started reading Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time’ (confession – I have completed only 4 of the 7 volumes till date) not knowing what to expect. I only knew that it was a ‘great work’, always to be found near the top of lists like ‘Greatest Novels of the 20th century’. The novel is about many things; it is about the workings of memory and perception, human desire, the nature of love, the deceptions of life in society, the relentless flow of time and the imperceptible changes wrought in its course. It is also about art and aesthetics as much as it is about anything else. I was to find my understanding of art expand and deepen as I read more of Proust. There are numerous references to painters, musicians, writers, actors, playwrights, poets and their works in the novel. Proust’s characters discuss and debate the merits of Chopin’s nocturnes, Hugo’s poems, Balzac’s Comedie Humaine and the paintings of the Dutch masters. They are all great readers and influenced by what they read. The narrator’s grandmother always carries with her the letters of Marquise de Sevigne and inserts quotes from this in each of her own letters. The Baron Charlus values above all the works of Balzac and Saint Simon. Swann the ultimate aesthete falls in love with a woman because she resembles to him Botticelli’s portrayal of Zipporah. There is a rich analysis of works of art and the effect they produce, in terms of both subjective experience and the wider effects they have on society as a whole. When the narrator watches a famous actress, Berma, in one of Racine’s plays we are made to feel his excitements and disappointments, his pain in trying to discern from her expressions and gestures, from her tone and diction the superiority of her talent, and his pleasure in finally realizing what it was that made her performance ‘sublime’. We learn how Beethoven’s Quartets were ahead of its time, not because the people of that time could not appreciate its greatness, but because,

It was Beethoven’s Quartets themselves that devoted half a century to forming, fashioning and enlarging a public for Beethoven’s Quartets, marking in this way, like every great work of art, an advance if not in intellectual merit at least in intelligent society, largely composed today of what was not to be found when the work first appeared, that is to say of persons capable of enjoying it.

There are four main fictional artists in Proust’s novel, Bergotte the writer, Elstir the painter, Vintenuil the musician and Berma the actress. It is through them that Proust formulates, explicates and elaborates on his notions about art. For Proust artistic reality is “a relation a law joining different facts” and that kind of reality requires style which is itself a series of connections in the material. Style is the essence of a work of art, and that style is the outcome of the individual and creative genius of the artist. The artist’s style is unique; it comes at first as a shock and seems incomprehensible because no one before this artist has sought to interpret the world in this way. All original painting or music or literature must at first seem strange because the images they conjure up are different from what we are accustomed to and which we consider as reality. We are conditioned to see the world in a particular way; it is an unconscious inheritance that we cannot easily disown. It is the artist who transforms what we know as reality and thus opens our minds to new worlds and this transformation or metamorphosis is effected through style. Proust compares the work of an artist to that of an oculist fitting us with new glasses to see with –

The course of treatment they give us by their painting or by their prose is not always agreeable to us. When it is at an end the operator says to us: “Now look!” And, lo and behold, the world around us (which was not created once and for all, but is created afresh as often as an original artist is born) appears to us entirely different from the old world, but perfectly clear.

The young narrator Marcel first discovers the pleasure of style through Bergotte. He is at first thrilled by certain passages in which he finds “a certain taste for uncommon phrases, bursts of music, idealist philosophy, a hidden flow of harmony”. He later learns to recognize this style, this “ideal passage” in every one of Bergotte’s books, thereby adding a certain density to and enlarging his own understanding. But this understanding was to get deeper, more refined. Marcel meets Bergotte at one of Mme Swann’s lunches and hears the writer in conversation. He finds Bergotte’s speech to be entirely different from his way of writing and therefore at first distressing. It did not appear to have the ‘Bergotte’ style. This disappointment lay in not grasping the true nature of his art. The mere adornment of prose with his images and ideas, the appropriation of his style by mediocre writers leads to nothing but lifeless imitations. The genius of Bergotte lay in his extracting from reality certain truths, discerning in all things certain forms, discovering certain relations between facts, the expression of which results in the ‘Bergotte’ style. It was the discovery of the equivalent of his literary style in his speech that gave Marcel the key to appreciating Bergottes art. A great writer is then not one who thinks of the beauty of his language. The beauty of their language is the result of a creative act, of seeking to give expression to an external object of which they are thinking.

Proust modeled Elstir on the great impressionist French painters of the latter half of the 19th century. The young Marcel, while spending a summer in the seaside resort town of Balbec gets to know the master painter Elstir. Through his paintings, Proust further develops his theme of art and style. Marcel, while visiting Elstir’s studio is held captivated by his recent seascape, the “Carquethuit Harbour”. In this painting, land is portrayed in marine terms and the sea in terms of land. The description of the painting is vivid and thorough; it easily fills up 20 pages. The effect of Proust’s writing is that the impression which we would have felt had we actually seen this painting, the visual effect, is replicated but by using only words. Here is one example of the description of the paintings transformation of land into sea and sea into land –

The men who were pushing down their boats into the sea were running as much through the waves as along the sand, which, being wet, reflected their hulls as if they were already in the water. The sea itself did not come up in an even line but followed the irregularities of the shore, which the perspective of the picture increased still further, so that a ship actually at sea, half-hidden by the projecting works of the arsenal, seemed to be sailing across the middle of the town;

Edouard Manet’s Port de Bordeaux: considered by many to be the inspiration for “Carquethuit Harbour”

The object of this metamorphosis is to give back to us our first impressions of nature, capture on canvas our perceptions in the instant before reason and intellect intervene. Intellect starts the process of classification and categorization, of giving names – sea, land -, of eliminating things which do not fit into the picture we thus construct for ourselves. The significance of Elstir’s style lay in reversing this process, of removing names, and thus presenting a pristine view of nature, of nature as she is.

Marcel while watching Berma in Racine’s ‘Phedre’ for the second time is finally able to discern what it was that made her a great actress. Earlier he used to deduct the part of Phedre itself from the actresses performance of it, in order to isolate her talent. This led to a disappointment. At the second viewing he was able to perceive that the talent he was seeking to discover outside the part itself was indissolubly one with it. Her diction, her attitudes, her gestures and the tone of her voice had become so completely absorbed in the part she was playing, so immersed in what she was interpreting so as to become nothing but a window opening upon a great work of art. Marcel then asks himself the question, “This genius of which Berma’s rendering of the part was only the revelation, was it indeed the genius of Racine and nothing more?” For which, he has the epiphany –

I realized then that the work of the playwright was for the actress no more than the material, the nature of which was comparatively unimportant, for the creation of her masterpiece of interpretation just as the great painter whom I had met at Balbec, Elstir, had found the inspiration for two pictures of equal merit in a school building without any character and a cathedral which was in itself a work of art.

Style and substance are thus false dichotomies. When they are seen as distinct, when we seek to separate the technique of the brushstrokes, the rhythm of a sentence, the intonation of voice, from the underlying reality they seek to convey, what we get is merely craft. Such craft is sterile because it is mindless. The aesthetic pleasure they seek to convey is hollow. There can be no progress with craft because it does not contribute to our understanding of life, of the world. There can be a school of craft, a tradition of craft because they seek to perpetuate a reality already known. We have to wait for the next artist to reconstruct our world. We cannot know what that world will be like because we cannot predict the style of the artist. For the artist substance is in style as life is truly lived through art. We acquire a true knowledge only of things that we are obliged to create anew by thought and which is incommunicable save by the channel of art.