Painter as Documenter – Van Eyck’s Revolutionary Arnolfini Marriage of 1434

Now, let’s get on the painting proper. This is the official portrait of the wedding of a rich young merchant named Arnolfini. He commissioned the painting and paid the high fee the artist must have demanded for it. Be in no doubt then, he is a real-life personality and this is exactly how he and his bride looked. They could be recognized on the basis of this picture just as easily as an emigration officer at an airport today would be able to verify someone’s identity on the basis of his passport photograph. They are posing in their bedroom, which in those days also doubled (during the day) as a sort of drawing room to receive friends and relatives. It is a somewhat small room unlike the capacious interiors the painter would have seen in the houses of the aristocrats or the bishops of the Church. But, for all that, it is a luxuriously furnished room and everything here (including the clothes they wear) declares the freedom from budget-consciousness that this couple enjoys. In fact the man is so well off that he can afford oranges (seen here on the window-sill and sideboard) imported from abroad – maybe from Spain – and that too, off-season, in the midst of the northern winter as evidenced by the warm clothing he wears.

What is an Italian like Arnolfini doing in the Flemish town of Bruges? Simple – he is an international businessman, belonging to one of Italy’s leading business families, the Arnolfini, who had trade interests all over Europe – they were into shipping, customs and clearance, multilateral exports and imports, and, probably war financing. (Unfortunately, we don’t have his first name; and so, which of the two Arnolfini brothers living then in Bruges this one happens to be, we just can’t say).

Now this man from the house of Arnolfini is marrying a local Bruges girl and wants the marriage documented. We can see that it is with his left hand that he is taking his bride’s hand. That means this is a category of marriage that is legally called a morganatic marriage. He is marrying outside the social and economic echelons of the great Italian mercantile families. By opting for this, he hopes to assure anxious souls within his large business family that in the event of his demise, it is only his personal wealth and titles that will pass on to her and to any of his children borne by her ; the family’s fortunes are not exposed to any risk.

That said, why does this Arnolfini scion want the picture painted? Is it the equivalent of the wedding album of our times, full of stored special moments to aid memory in later times? That may certainly be a reason but it is not the reason. What prompted the commissioning of the portrait was in all likelihood the need for visual documentation in the presence of witnesses to affirm the legitimacy of the marriage. By the way, this is not a private version of a public wedding ceremony conducted at church. It is a private wedding inside the home. The act of posing for the portrait by Van Eyck is all the ceremony there will be. Thus the act of painting is also an act of giving legal force to the pledges these two have made to each other.

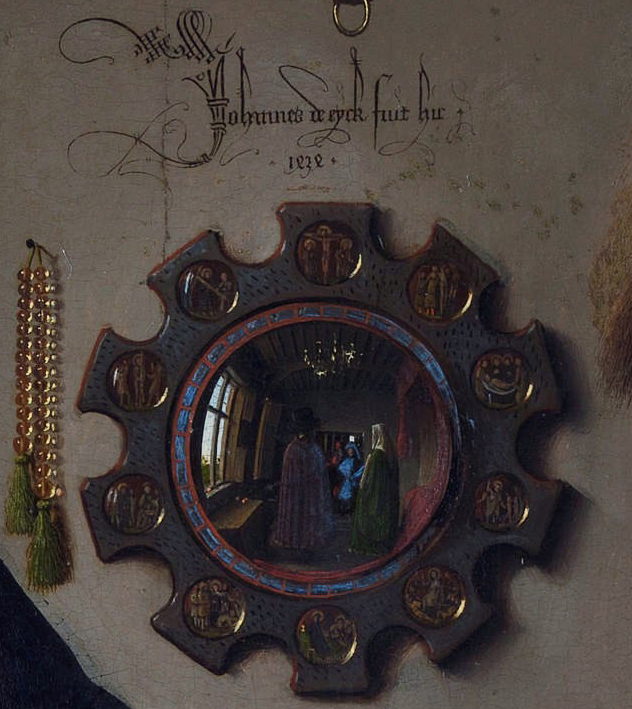

This brings us to the question of the role of the church in the whole matter. Are we witnessing a complete bypassing of the need for ecclesiastical sanction? Is such a ceremony to be read then as the triumph of the secular over the sacred? Well, that would be going a bit too far. All we can say is that this opens out before us as a zone of ambivalence. It may come as a surprise to many to learn that in those pre-Reformation times the church had no problem accepting the legitimacy of such a ceremony as long as at least two men of honour bore witness to it and the couple turned up together to receive communion at the local parish church on the first Sunday following the wedding. Now, all those conditions are fulfilled here. The man is swearing a solemn oath with right hand upraised. There are two witnesses. Look carefully at the convex mirror on the back wall and you will see the reflection of the painter and a friend. Here is also an instance of the self-referentiality of the work – miming its own origins – a sort of meta-painting analogue of the meta-fiction we have come to associate with writers like Nabokov and with the postmodern artists of our times.

The painting’s status as legal document is further reinforced by the painter departing from realism for once in writing his name across what is represented as the wall in the painting. Of course there is no way he would have written it on the actual wall. This can be taken in one sense as a painterly conceit. But there is another sense in which he is merely signing a legal document. (It is actually a declaration in Latin which reads “Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434,” meaning “Jan van Eyck was here, 1434”)

Scenes from the passion of Christ on the mirror frame, as we have already observed, reproduce in the home the atmosphere of the church and assure us that these are people still connected to the church. The single candle burning in the chandelier above is a symbolic representation of the Light of God, from whose presence nothing can be hid and so God is acknowledged as the ultimate witness.

Nevertheless, we can sense that the whole thing does represent a personalization of faith that has the potential to eventually lead to a reduction in the powers of the clergy. This was indeed to find historical realization in the Protestant revolution (the Reformation) spearheaded by Luther barely a century later. Individual and domestic forms of piety carry within them the potential to circumvent the mediation of an ecclesiastical hierarchy. Could this be a painter’s discernment of the seeds of change beginning to sprout? One can only wonder.

Whatever may be our take on that question, we are left in no doubt that Van Eyck enjoys the corpus of images, metaphors and symbols that the Judeo-Christian tradition has bequeathed to him because he deploys quite a few of them in the painting. This opens up several options for interpretation. Take, for example, the wooden clogs in the foreground. They seem to be in the kind of position that suggests the great haste with which they were shaken off. Was the man stung by some uncharitable remark into quick action towards formalizing this relationship? Or is this an allusion to Moses in the desert ordered by God in the “burning bush” to take off his sandals because “the ground thou standest on is Holy ground”? The painter seems to be suggesting that this is a sacred act and hence domestic life is as sacred as the hallowed lives of those devoted to the church.

The dog, so very realistically painted, is also a symbol – and a very conventional one at that – standing for the woman’s declaration of her fidelity to him. The bed holds promise of legitimate offspring.

A common misconception that many viewers entertain is that the young woman looks pregnant and this leads to the conjecture that the man is owning up and taking responsibility but that love may have had little to do with it. Art experts (and experts of period clothing) are, however, unanimous in their conclusion that the long and heavy train of her expensive wedding gown can only be held up that way during the ceremony.

Debates rage on about the interpretation of this or that detail in the work and these may well continue infinitely, but Van Eyck’s masterpiece will always ride above them in its artistic integrity, refusing to be reduced to any single hermeneutic position. The passing of six centuries seems to have had not the least success in eroding its appeal, thus making possible one more example of the power of good art to travel through time, radiating new meanings to ever newer generations.

Pages: 1 2